What good is strategy to museums?

Join me next week as we kick off Wardley Mapping for Museums (2.0).

Back in March of this year, MAP’s seasonal purpose was… mapping! And because I teach something called “Wardley Mapping,” which is all about strategy, Kyle invited me ‘round to run a workshop.

I must confess, I had no idea whether to say yes. “After all,” I thought, “what use do museums have for strategy?” But I’m glad we did it, because as we discovered over the course of the workshop, the answer to that question is, “Quite a lot, actually.”

So let’s talk about strategy. Firstly, what the heck is it? What is strategy, even?

Instead of boring you with a mind-numbing definition that you’ll never use, I’m going to dodge the question. Strategy is first and foremost a buzzword. So don’t sweat it.

There’s still some stuff behind that word, though, that is worth “getting,” so hold that thought. We’ll return to that question, by way of a different question.

In order to talk about strategy, we need to talk about why we bother to create organizations. Put another way, “Why does our organization exist?”

When I ask this question in the private sector, here’s what usually happens.

25% of people answer bluntly. “Make money.” “Profit for shareholders.” (Snooze.)

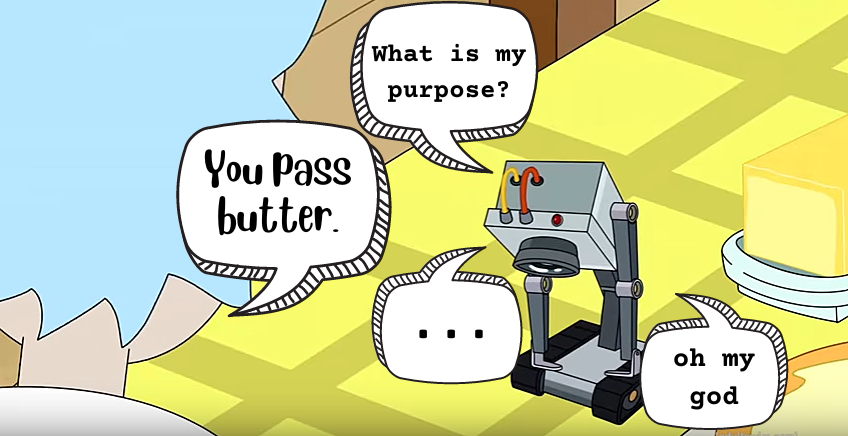

Another 25% of people just describe the company’s function in the market. “Sell widgets.” “Make software.” “Pass butter.” (Snooze again.)

The remaining 50% make an earnest but unconvincing attempt to regurgitate the nice-sounding words on the company website. (Points for effort, but still, snooze.)

I don’t mean it to be a trick question, but it seems to be a question that leaves people feeling tricked. Nevertheless, we forge onward.

“How does your organization’s purpose measure up, in the grand scheme of things?”

A less polite way to ask this question is, “Given [insert current events here], why should anyone care whether your organization continues to exist?

Against this bleak backdrop, I broaden the question to relieve a bit of the pressure.

“Why do organizations exist in general? Why do we bother to organize?”

I don’t want people to flounder too long here, because I want them to find a bit of hope amidst the trail of existential wreckage left by our conversation so far.

“We create organizations, because we can accomplish more TOGETHER than we could ever accomplish separately!”

You might be thinking, “Well, yeah, obviously.” And it is the obviousness of this idea that helps us start connecting the dots back to strategy.

In order to accomplish greater things, organizations have TWO essential functions:

Gathering energy (the labor of the people doing the work), and

Directing that energy at something (a specific purpose).

If organizations exist to gather and direct human labor towards accomplishing greater things than any one person could accomplish, then that leaves a very important question unanswered.

“WHAT do we wish to accomplish, together?”

In other words, how will we use our labor? Towards what purpose?

How do you even make that choice?

But it doesn’t end there. Even if we decide what to accomplish, how good are we at directing our labor towards it?

If the answers to our earlier question are any indication, the answer is “terribly.” But let’s make it abundantly clear with a throwback to physics class.

Imagine you have a piece of paper and a pin. How easily could that pin puncture the paper?

Now, imagine instead trying to puncture the paper with your closed fist. How would that compare?

The secret behind what successfully punctures the paper is hidden in the following equation: P = F / A

Pressure (P) is equal to the force applied (F), divided by the surface area (A) over which it is applied.

When the force is focused onto a specific, small area, like the end of a pin, the pressure it creates is huge! (The pin punctures the paper with ease.) But when that force is diffused across a larger area, like with your closed fist, the pressure is much smaller, and much less effective.

This equation applies to organizations, too, where pressure (P) represents how much the organization can accomplish, given its labor force (F), and the purpose surface area over which that labor is directed (A).

Here’s the sad truth: Most organizations scatter their energy instead of focusing it. They distribute whatever force they have over a huge, unfocused surface area, making achieving any kind of impact immensely difficult.

And here we finally arrive at strategy.

Yes, it’s a buzzword. But if it were a concept worth learning, it would have to do with how we manage the Force and the Area in our organization’s pressure equation.

The tool I teach, Wardley Mapping, helps visualize this challenge. It’s how you “show your work” when it comes to making sure that what you do — how you direct your scarce resources and over what surface area of possible purposes — makes sense.

The best part is that this version of “strategy” is not just for people with ultimate authority. Anyone can and should manage this equation, in whatever scope they make decisions. All it takes is for one person, whoever and wherever they are, to map things out, make the best decision they can, and share what they learn.

So, does all this matter to museums?

It depends on how you answer these questions.

Why does your museum exist?

How does that measure up, in the grand scheme of things?

What does your museum wish to accomplish?

How well does your museum direct labor towards that purpose? (Is it scattered, or is it focused?)

Let us know what you discover!

In the meantime, if you want to learn more about strategy, Wardley Mapping, and how all this can help your museum, consider joining our upcoming hands-on lab, Wardley Mapping for Museums, which starts next week.

All the best,

Ben

Related Letters