Listening Deeply: A Key to Driving Behavior Change in Museums

When museums try to cultivate new audiences, strengthen existing relationships with communities, or increase engagement, what they're really talking about is behavior change.

How do we know when we've achieved any of these kinds of goals?

We see it in the way people behave. Not their opinions or how they say they feel about us — a change in behavior is what tells us we're making progress.*

It can be hard to change our own behavior, much less other people's.

If we want people to consider the museum a viable support for their goals, we often have to piggyback on some external trigger beyond our control.

Example: Jerry has family from out of town visiting this weekend and wants to keep them entertained. Normally, Jerry is busy living life, and the museum just isn't part of the consideration set (see "beliefs" in the progress cycle diagram). Jerry has a new goal (Show Family a Good Time), which lends itself to new choices and a behavior change (Visit the Museum for the First Time in a Long Time).

I suppose it's possible for a museum to insert itself into Jerry's world and somehow trigger a change in behavior without any other external influences. Maybe. But that's an expensive, brute-force approach in the sense of effort and resources (time, money, and perhaps goodwill). It's better to look for those moments when Jerry is looking for some new alternative to address a change in circumstances. The museum can then be a form of support in response to a pre-existing change in goals rather than trying to change someone's goals and support that goal.

So, the museum's goal can shift from trying to change people's stated opinions about the institution (marketing for the sake of marketing) to identifying when, where, and how it can show up as a form of support for particular goals.

Museums can do that through listening. But the way most museums listen today is not well-suited to behavior change.

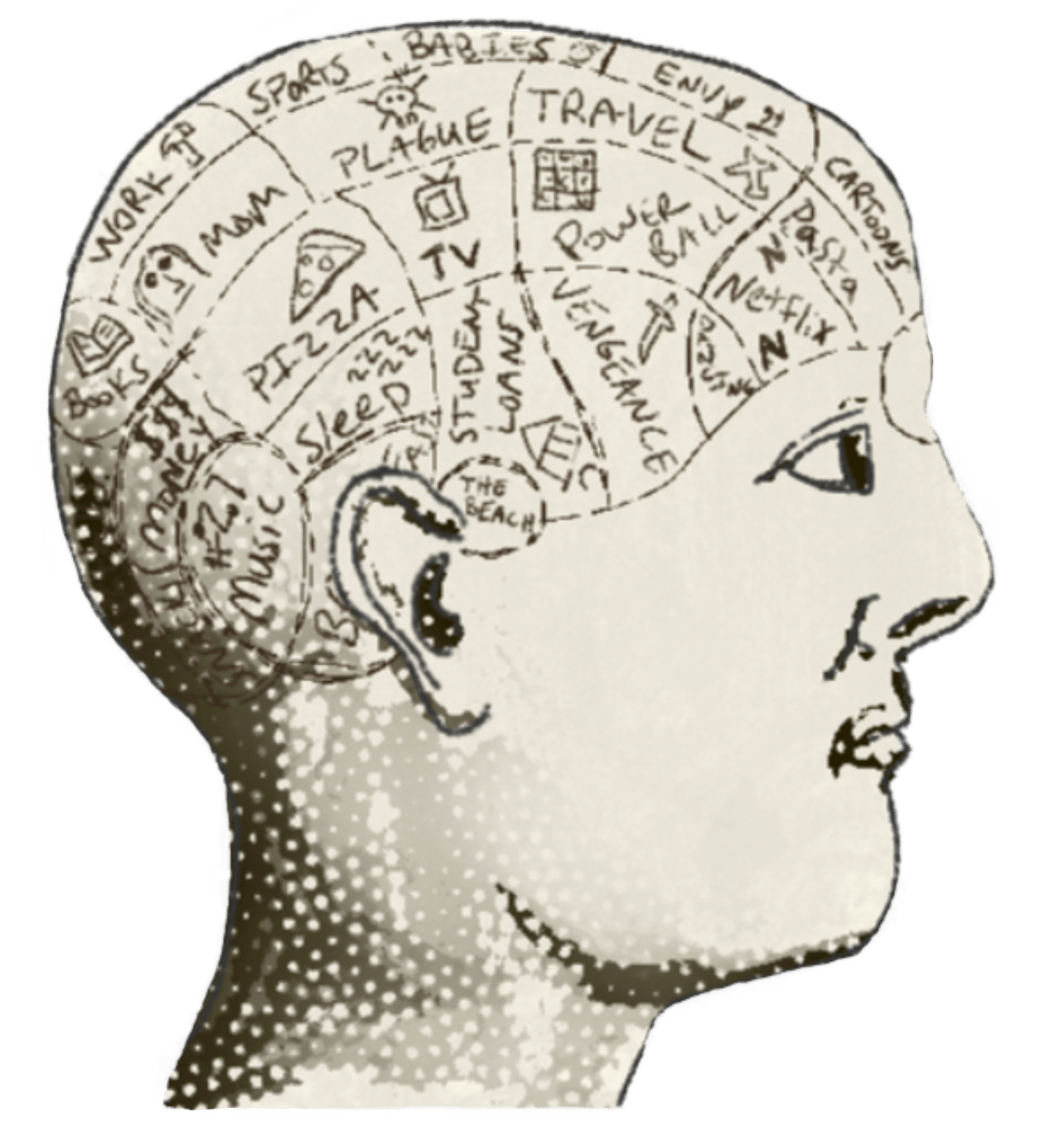

We can't ask people what they want from our museums because people don't know. We can't ask people what they like or what they might do in the future because the things we think we do in general or in principle don't align with what we actually do in a specific circumstance. These kinds of listening exercises are centered on the museum — They don't surface opportunities to support Jerry on Jerry's terms.

We can adopt a better approach — Listening for Interior Cognition (or "Listening Deeply").

Listening for Interior Cognition is anchored to a person's goal (not museums' goals, like engagement). This kind of listening is how we can identify pre-existing opportunities for relevant support — A better approach than hoping we can advertise our way to relevance.

The MaP Community is hosting a free event on Listening for Interior Cognition later today. If you'd like to learn more about the method we use to identify ways to support people's goals, I hope you'll join us.

RSVP

Kyle

*Marketing folks reading this may object: "But brand perception is important. Sentiment and satisfaction matter, too!" Yes, but how are those perceptions, beliefs, and feelings expressed? Repeat visitation, word of mouth, selfies shared … Those are all behaviors. A positive sentiment shared in a satisfaction survey is a tree falling in a forest with no one but the museum to hear. Sentiment matters, but it's the expression of that sentiment that matters — the behavior of sharing it with others. Otherwise, its impact is minimal.