Museums are Perfectionist Control Freaks

In 2010, Nina Simon published The Participatory Museum and taught museum folks that we need to invite visitors to “create, share, and connect with each other around content.” Since then, many of us have internalized that museums should give visitors more control over content.

The issue is, we don’t.

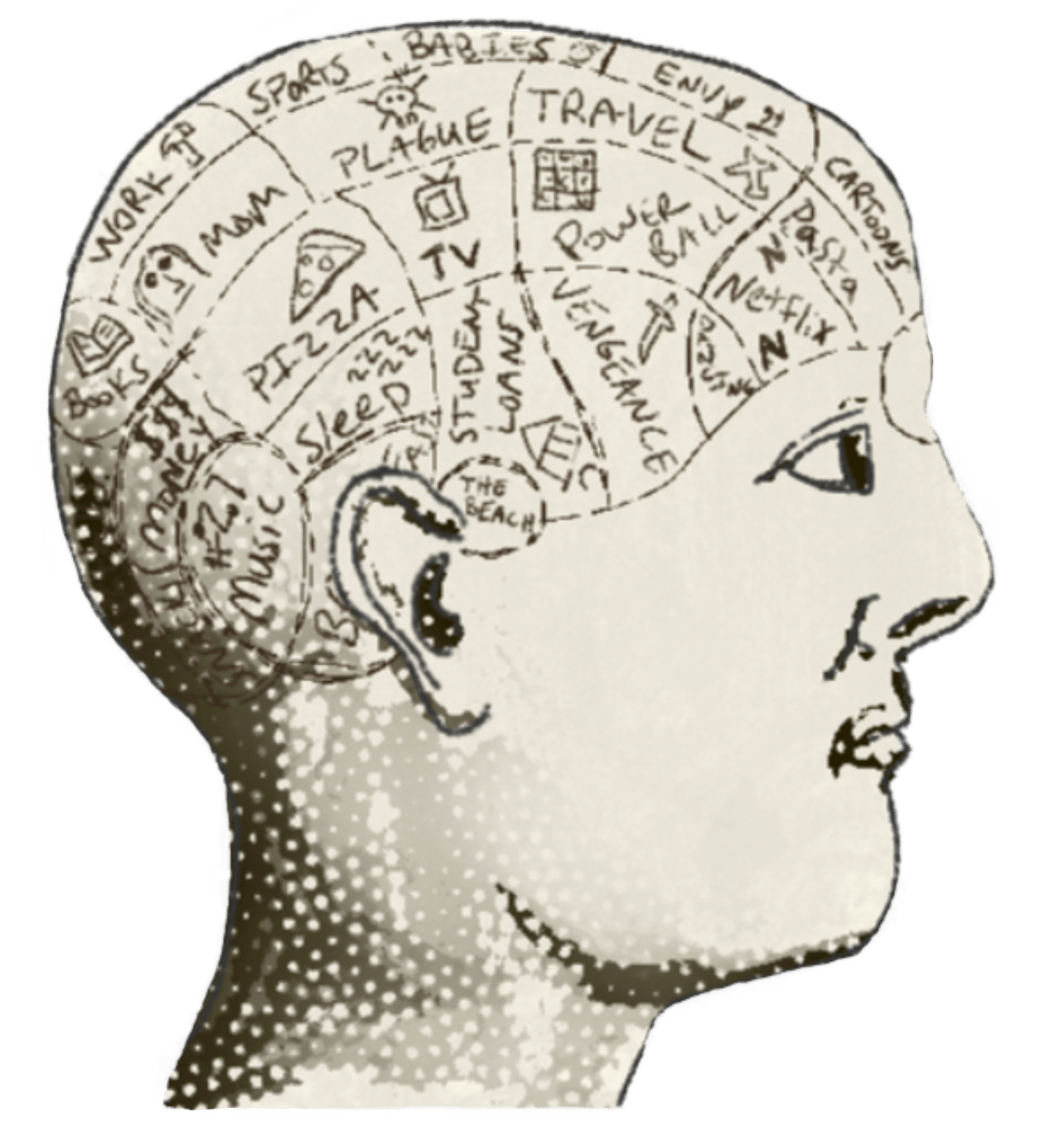

I keep asking myself, “why are museums still stuck in 2009 with the premier of Glee and Obama’s first inauguration (yah, it’s been that long)?!?” One answer that I keep coming back to is that museums are perfectionist control freaks.

Perfectionist control freaks: A brief history

It makes sense - museums were designed to control people. In her book Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, museum studies scholar Eileen Hooper-Greenhill argues that our modern museums are based on the model of early nineteenth century French museums. The French government invested in these museums to mold French people into “good” citizens. They empowered experts (curators) to organize collections and tell visitors what to think about the world (interpretation). Through their interpretation, the experts encouraged individuals to obey societal norms, such as those around dress, communication style, physical gesture, family structure, sexual ethics, gender presentation, and more. They marked people and objects that strayed outside of these norms as disruptive or dangerous. The French model spread throughout Europe, leading to many of the best practices and physical infrastructure of nineteenth and twentieth century museums. Although the way we structure museums has significantly evolved over the past two hundred years, much of our practice is still rooted in this public museum model.

Loss aversion as a root cause

I believe another reason that museums are perfectionist control freaks is that a lot of museum folks suffer from personal perfectionism complexes. We are NERDS. Museums are filled with goody-two-shoes A+ students, not party kids who break curfew. Over and over again, I see museum professionals, particularly executives, who are so afraid of making a mistake, so scared of straining relationships with existing visitors and donors, that they just keep doing things the way they always have. “At least it won’t get worse,” they think.

Except, it is getting worse.

The population of the U.S. is increasing but, since 2009, the percent of Americans who have visited a cultural organization has decreased by nearly 3% and the pandemic is making these numbers even more abysmal.

What can we do about this? How can we face our history and own fears of failure?

Let me tell you a story.

Perfectionist Control Freak, C’est Moi

When I was a high-strung dork in high school, my favorite teacher would regularly remind me, “the perfect is the enemy of the good.” He would quietly try to convince me to go to parties and to do stupid teenager stuff. He knew that, because I spent all my energy trying to be perfect, I was too afraid to take risks, too scared to put myself out there. I was too frightened of failure to grow.

When I finally took his advice in college, I became a grounded person and a loyal friend. Instead of the academic and professional failure that I had feared, I grew into an empathetic and discerning historian.

So, what is the museum-scale equivalent of going out to a bar for the first time and (OMG) getting a bit tipsy?

Four prescriptions for perfectionists

1. Buffoonery

If you want to loosen up and take yourself less seriously, the first piece of advice that any halfway decent self-help book will give you is to poke fun at yourself - publicly. It’s time for museums to embrace their inner class clown.

Take the Museum of English Rural Life (MERL) Twitter account, for example. The MERL has a serious and important mission, “to explore how the skills and experiences of farmers and craftspeople, past and present, can help shape our lives now and into the future” and it is connected to a good research university. Yet, the MERL’s twitter account embodies the class clown aesthetic. In one viral tweet, the museum poked fun at a doodle of a chicken in trousers that they found in a farm boy’s math book from the eighteenth century. The tweet became so popular, the MERL started selling merchandise with the doodle. With 155,800 Twitter followers and counting, the MERL’s clowning around is helping it fulfill its mission.

2. Rebellion

Another way to get comfortable with your institution’s imperfections is to rebel against the rules a little. Think like a teenager does about her parents’ rules: what’s a “do not cross this line” at your institution that you’ve always thought was a little stuck up and silly. Can you bend it? For instance, maybe your conservators don’t like it when visitors eat in the galleries. You could create a program where you throw a tea party near the eighteenth century British paintings. I’m not saying you should go so far as to throw tea sandwiches at the art, I’m saying stuff your face with cookies and clean up really really well afterwards.

3. Just plain fun

Or, take yourself less seriously by just trying to have some good old fashioned fun. Newsflash - visitors want to be entertained. Try creating a program or exhibit element because you think it’s nifty and don’t focus on specific learning or experience goals for it. You could put a bean bag chair in front of your favorite object. Write sarcastic responses to labels on sticky notes and put them on the wall. Maybe you could also put out a table out with some sticky notes and pens for visitors and invite them to have at it. Observe visitors as they interact with your experiments and see what happens.

4. Vulnerability

Another way to take yourself less seriously is by showing visitors how the sausage is made. Hooper-Greenhill argues museums have a long history of hiding how we interpret collections and information from the public - a tradition that got us into this perfectionism mess in the first place.

If you don’t already have behind the scenes tours, you may want to start offering them. One of the most popular events at The Field Museum is their Members’ Night, when they invite members to go through the areas of the museum where they do the work of interpretation, like the exhibit fabrication shop and the conservation labs. Visitors chat with scientists, conservators, exhibit designers, security personnel, educators, and everyone else who makes the museum possible.

Toward a less control-freaky future

So take a deep breath, clown around, rebel against the rules, have some fun, and invite your visitors to join you.

When you invite visitors to the party, you will likely find that they are more invested in your institution. They may even discover a place where you could use their skills. In other words, if you get better at entertaining visitors and you’re willing to show them how you do your work, they may uncover opportunities to co-create the future of your institution together.

Isabel